Public health systems, health projects and programmes have most often been constructed in a narrow bio-medicalised framework, with a focus on disease rather than health and well being, despite the 1948 WHO definition which tried to shift focus to all aspects of well being – physical, mental and social. The Alma Ata declaration began a new approach by shifting the focus to social justice, equity, social development and rights. Civil society and social movements have tried to take this forward with limited success because the biomedical paradigm is so deeply entrenched. At the Global Forum for Health Research this paradigm was presented in greater detail to shift the bio-medical pre-occupation in all aspects of health systems – structure, focus, dimensions, technology, type of service, link with people and research (1).

The Paradigm Shift Table

| Approach | Biomedical | Social community |

|---|---|---|

| Focus | Individual | Community |

| Dimensions | Physical / Pathological | Psychosocial, Cultural, Economic, Political, Ecological |

| Technology | Drugs / Vaccines | Education and Social Processes |

| Type of service | Providing / Dependence Creating / Social Marketing | Enabling / Empowering / Autonomy building |

| Link with people | Patient as Passive Beneficiary | Community as active participant |

| Research | Molecular Biology Pharmaco- therapeutics Clinical Epidemiology | Socio-epidemiology, Social Determinants, Health Systems, and Social policy |

This paradigm shift must be appreciated by policy makers if social justice in health through health in all policies is to become a reality. They must be encouraged to appreciate the seven shifts (2)

- A shift in focus from individual to community

- A shift in dimensions from physical and pathological to broader psychosocial, cultural, economic, political and ecological dimensions.

- A shift in technology from drugs and vaccines to education and social processes.

- A shift in the type of service from social marketing and providing models to enabling, empowering and autonomy-building processes and initiatives.

- A shift in the attitude of people from patients and/or passive beneficiaries to people and communities as active participants.

- A shift in research focus from molecular biology, pharmaco-therapeutics and clinical epidemiology to socio-epidemiology, social determinants, health systems and social policy research.

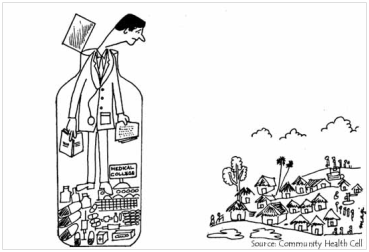

- A shift in structure from institutional based (hospital and health centric) work to community based and led approaches.

A beginning has been made in the WHO SEARO region, which brought together epidemiologists from the region to discuss ‘Application of Epidemiological Principles for Public Health Action’. In the conclusion of the meeting the participants recommended – ‘the scope and reach of epidemiology, which is an integral part of public health, must be expanded to include the study of social, cultural, and constitute the keystone for use of evidence for development of public health policy…..such an approach will help in moving beyond health problems per se to new complex social and human developmental challenges such as the current crisis and threat to public health posed by the global financial meltdown and climate change’.(3)

- Narayan R. What evidence? Whose evidence? Who decides? Challenges in health research to achieve the MDGs and respond to the 10/90 gap in Beverly PS, (ed) Health Research for the Millennium Development Goals. Forum 8 Mexico, Geneva, Global Forum for Health Research 2005. 29-30. ↩︎

- Narayan, R, Revitalizing primary health care: How can epidemiology help, The proceedings South East Asia Regional Conference on Epidemiology, New Delhi, 8-10 March 2010, WHOSEARO, 2011. www.searo.who.int/LinkFiles/CDS Epid meet C&R 26-27feb09.pdf [accessed 26th Sept 2014] ↩︎

- WHO SEARO, Conclusions and recommendations, Regional meeting on application of epidemiological principles for public health action, 2009. [accessed 26th Sept 2014] ↩︎